© October 25, 2025 by John Kotuby

Saltwater flats fishing has become my favorite pastime in the last 6 years since I’ve moved to Florida from Connecticut. I have had good luck catching Snook and Speckled Trout, the Ambush Predators of the backwaters. I attribute that to the fact that up north I fished primarily for Largemouth Bass and Trout… also Ambush Predators. So the techniques I used for Bass and Trout up North also worked for me in the Florida backwater. I could catch them by retrieving jigs, worms and lures rather quickly. Yes, I have caught some very nice Redfish also, but not as often as I would like. Even though the locals tell me “Oh, Redfish are easy”. I have also heard “If you are fishing slowly and haven’t gotten any bites… fish slower.”.

So let’s dive into the Feeding Habits of Redfish so we can catch more of them… and bigger ones.

Of all the inshore characters that nose around our Southern coast, Redfish have the most curious table manners. They don’t blitz like mackerel or sky like tarpon. They browse, they investigate, they work the bottom. Figure out what they’re searching for, and you’ll figure out how to feed them.

In this long guide I’ll break down where Redfish love to eat, how tides and temperature shuffle the dinner table, and why a slow retrieve often flips the “eat” switch. We’ll lean into the biology and behavior that actually drives their feeding, then I’ll sprinkle in quick technique notes to help you match the moment on the water.

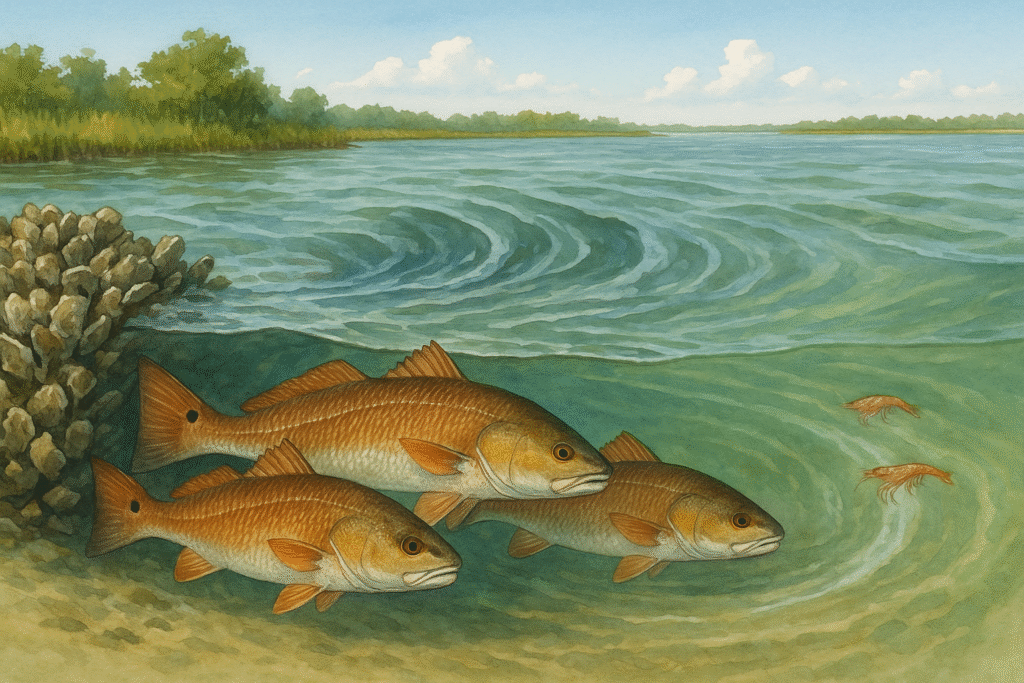

Classic feeding flat: knee-deep grass with gentle tidal flow and nervous bait flicking on top.

Meet the Forager: The Redfish Feeding Toolkit

Redfish (Sciaenops ocellatus) are built for rooting out small, crunchy calories. Their mouth is slightly subterminal—aimed down at the buffet line—and they carry a powerful set of “crushers” in the back of their throats for cracking crabs and shrimp. Their lateral line is a pressure-sensing superpower that detects tiny vibrations made by scuttling crabs and flicking shrimp. Combine that with keen low-light vision and a preference for edges and seams in current, and you get a fish that feeds patiently, deliberately, and close to the bottom.

Primary prey: juvenile blue crabs, fiddler crabs, mud crabs, shrimp, and seasonally small baitfish like mullet and menhaden.

Where the groceries live: grass flats, marsh edges, oyster bars, sandy potholes, and current seams near structure.

How they hunt: slow cruising, tailing while pinning prey, and ambush positioning that lets the current bring food to them.

Technique note: Because Redfish feed down and often into the current, a presentation that starts up-current and drifts or crawls naturally toward the fish will out-fish cross-current skating almost every time.

Technique note 2: Redfish WILL strike topwater lures mostly on late summer mornings when they are cruising the grass flats just after an incoming tide has raised the water level to around 2 feet, exposing delicious critters to crunch on. The lures will mimic running Mullet, which Redfish feed on when mullet are migrating in-shore during late summer and early fall.

Location, Location… and Conditions

Finding Redfish that are actually feeding is a game of habitat + conditions. Here’s the short list I run through on every trip:

1. Grass Flats (6–24 inches on incoming tides; 2–4 feet on mid tides)

Redfish push shallow with the rising tide to nose through grass for crabs and shrimp. Look for:

- Micro-flow: gentle current that shivers the grass tops. This allows for easy hunting.

- Life cues: Birds tiptoeing, shrimp clicks, bait dimpling, and tails waving. No life = no food.

- Bottom mix: Patches of sand in grass — natural strike zones. Target edges of sand openings.

Tailing Redfish feeding the incoming tide over shallow grass flats

2. Marsh Drains and Creek Mouths (outgoing tide)

As the tide falls, everything that lived up in the grass gets flushed out. Reds set up at the drain, slightly down-current or tight to the seam.

- Prime stage: mid to late outgoing.

- Best clues: “pushes” of fish, bait piling at eddies, and the thump-thump feel when your jig ticks oysters.

3. Oyster Bars and Edges

Oysters are crab factories. Reds hold on the down-current side, saving energy while surfing the buffet line.

- Approach: Long cast up-current with a lure that will crawl across shell, not skip above it.

- Bonus: After a boat runs over a bar, give it ten minutes. Reds will slide right back.

4. Channels, Troughs, and Ledges

When water turns chilly or blazing hot, Reds slide deeper for stability. They’ll still feed—just slower and tighter to bottom.

Tailing Reds advertise an active feed. Aim beyond them and slide your offering into the zone.

Why Tides Call the Dinner Bell

Tide is the conveyor belt that brings food to Redfish. It also tells us where they’ll station and how fast they’ll eat. Think in stages:

Flooding (Incoming) Tide

- Early flood: Reds lift off edges and start nosing onto the first shelf. Subtle shrimp imitations shine.

- Mid flood: They spread across the flat following bait.

- Top of tide: Feeding often becomes selective until water begins to fall again.

Falling (Outgoing) Tide

- Early fall: Reds regroup near drains.

- Mid to late fall: The money window. Prey is flushed off the flats.

- Low slack: Slow-down mode. Reds settle in depressions or adjacent edges.

Technique note: Cast upcurrent and retrieve with the flow. Keep contact with the bottom but don’t plow—think “crawl, tick, pause.”

Slow Wins: The Biology Behind a Crawling Retrieve

Redfish are habitual “inspectors.” Two biological reasons explain why slow retrieves trigger more bites:

- Lateral-line targeting: Crabs and shrimp scuttle, stop, and flick. A lure that crawls with tiny hops mimics those pressure signals. Fast retrieves create unnatural vibration.

- Subterminal feeding posture: Reds point down when they feed. A lure crawling along the bottom stays in their strike zone. Faster retrieves lift the bait out of sight.

Add in the fact that Reds often feed in turbid water, and patience pays off. Count your pauses. Let the jig sit long enough to make you doubt yourself — then tick, that thud.

Water Temperature, Oxygen, and Seasonal Shifts

Redfish tolerate a wide range of salinity and temperature, but their feeding pace follows comfort and oxygen. The “happy zone” is roughly 70–85°F.

Below ~55°F, they slow and school tighter. Above ~88°F, they slide deeper to cooler, oxygen-rich water.

Season-by-Season Playbook

Clarity, Color, and Turbidity

Reds don’t need clear water to chew. Lightly stained water hides them and favors vibration-based feeding.

Ultra-clear days can make them spooky—dead-stick longer.

Chocolate milk conditions? Fish the edges where clean meets dirty.

Reds sit just inside the backwash of a down-current eddy, near an oyster bar, feeding on drifting shrimp

Reading Body Language: Signs of a Red in Feed-Mode

- Tailing: Head-down vacuuming—present quietly and almost motionless.

- Backing: Bronze back or dorsal showing—don’t spook them, just lead gently.

- Wakes & pushes: A steady push means cruising feeder.

- Pops & flicks: Bait showering near grass points = Reds shopping.

Brief, Condition-Matched Techniques

(We’ll dive deeper in future posts.)

- Flooded grass: 3–4″ shrimp or crab plastic, weedless. Tiny twitches.

- Oyster edges/drains: 1/8–1/4 oz jig head, tick shell, pause.

- Deeper troughs: Weighted fly or Carolina rig, slow crawl.

- Wind-against-tide seams: Spoons or spinnerbaits, slow and steady.

Putting It Together: Three Scenarios

A. Early Flood on a Thin Grass Flat

8 inches of new water, light wind, shrimp clicking. Reds rise off the trough. Cast 6–8 feet upcurrent of tails, let current carry, then one tiny twitch. Gentle lift for the hookset.

B. Mid-Outgoing at a Marsh Drain

Current roaring through, bait flickering. Reds stacked two feet off the heaviest flow. Cast 10 feet above the seam, count down, and tick bottom. Two slow turns, pause—thunk.

C. Post-Front Winter Midday

Bluebird sky, chilly morning, sandy potholes in 3–4 feet warming in the sun. Small crab imitation, long pauses, subtle hops. Watch your line—bites may feel like a slow pull.

Smart Positioning: Fish Like a Redfish

Imagine you’re the Red. Where would you sit to let the current do the work?

- Behind: oyster spines, grass clumps, mangrove roots.

- Below: tide rips, drops, deeper edges.

- Beside: seams where dirty meets clean, shallow meets deep.

Diagram: Typical redfish feeding stations relative to tidal current.

Salinity, Weather, and the “Why” Behind Good Days

Redfish tolerate salinity swings but prefer balance. After big rains, they shift toward passes where bait rebounds first.

Stable or slightly falling barometer + steady tide = confident feed.

Avoid bluebird, post-front “glass” days unless you’re stalking in ultra-shallow calm.

Common Misreads (and Better Reads)

- “No fish here—water’s too dirty.” → Fish the edges of dirty/clean lines.

- “They won’t eat—speed it up!” → Slow down. Count your pauses.

- “High tide means fish everywhere.” → Focus on moving water, not static high.

- “It’s hot—go super shallow.” → Dawn shallow, then follow them deeper.

Quick Gear Cliff Notes (Biology-Informed)

- Weights: Use the least weight that maintains bottom contact.

- Profiles: Crab and shrimp shapes rule; paddle tails in fall.

- Hooks: Weedless for grass; open for shell.

- Line: Sensitive braid + fluorocarbon leader to detect subtle bites.

Field Checklist: Fast Way to Find a Feed

- Is water moving?

- Where’s the edge?

- Do I see life?

- Can I cast upcurrent and stay low and slow?

- Am I pausing long enough for the Redfish to inspect?

Redfish reward anglers who think like naturalists and fish like chess players — patiently, one good move at a time. If you can match the biology (what they’re built to eat, how they sense it, and where current makes hunting easy) with calm, precise presentations, you’ll turn more lookers into eaters.

I hope you enjoyed this article and catch more fish because of it.

Tight lines!

John